Why Hospitals Want Patients to Pay Upfront

By John Tozzi

September 25, 2014 - Businessweek

Melody Rempe spends much of her day telling people who are about to go into

the hospital how much theyfll have to pay. As a patient financial counselor at

Nebraska Methodist Health System, she calls patients about a week before they go

in for procedures with estimates of their bills and what portion insurance will

cover. Although many are grateful, some cry or yell. gSometimes youfre talking

to them about the biggest thing in their life,h she says. Rempe says most calls

end well when she walks patients through the hospitalfs payment-plan options or

other financial assistance.

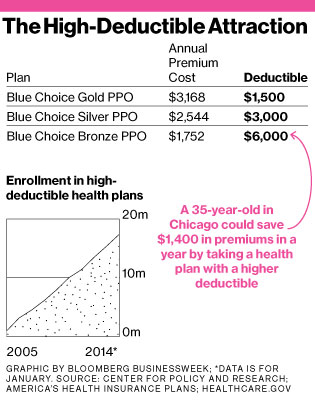

Hospitals have good reason to be concerned about their patientsf finances:

Even people with insurance are increasingly responsible for a big portion of

their medical bills. Among Americans who get health coverage at work,

41 percent have deductibles of at least $1,000 they must meet before

insurance starts paying. Thatfs up from 10 percent in 2006, according to

the Kaiser Family Foundation. Those with employer coverage are joined by

7 million new enrollees in Obamacare plans, which typically make patients

share a large chunk of costs. The average deductible in the most popular

gsilverh tier of coverage is $2,267, according to an analysis by the Robert Wood

Johnson Foundation.

Raising deductibles helps employers and insurers limit premium hikes. It also

shifts more of the risk onto individuals. That in turn boosts the chances that

doctors and hospitals wonft get paid. If a patient has a $2,900 deductible,

gitfs far more difficult to get that $2,900 from an individual patient than it

is from the Medicare program or from Blue Cross Blue Shield,h says Richard

Gundling, vice president of the Healthcare Financial Management Association, a

trade group. A March report on hospitals from Moodyfs (MCO), the credit-rating firm, was blunt: gTodayfs

high deductibles are tomorrowfs bad debt.h

gTell me what 28-year-old is going to be able to provide, especially in

this economy, $6,000 of their own money?h—Jan Grigsby, CFO, Springhill

Medical Center

Hospitalsf total cost of uncompensated care reached $46 billion in 2012,

equal to about 6 percent of their expenses, the American Hospital

Association says. Large for-profit chains such as LifePoint Hospitals (LPNT), which operates more than 60 medical

centers in 20 states, have felt the impact of rising deductibles.

LifePointfs bad debt related to copays and deductibles is running at

$25 million per quarter this year, up from $15 million per quarter in

2013, Leif Murphy, the companyfs chief financial officer, said on an earnings

call in July. He blamed the increase in part on the growing prevalence of

high-deductible plans.

As the mechanics of insurance policies become more complicated, Americans are

having a harder time understanding how their plan choices will affect their

finances. Only 14 percent of insured adults correctly understand insurance

jargon such as deductibles, coinsurance, copays, and out-of-pocket maximums,

according to a 2013 study published in the Journal of Health

Economics.

Many Americans arenft prepared for a medical emergency. Dr. Marilyn Peitso, a

pediatrician in St. Cloud, Minn., says parents often canft afford $300 to $400

for antibiotics to treat an ear infection. gFor young working families, this can

get to be a real financial burden, and it can make them less likely to seek

needed care,h she says. About 44 percent of households have less than three

months of savings, according to an analysis by the Corporation for Enterprise

Development, an antipoverty group. gTell me what 28-year-old is going to be able

to provide, especially in this economy, $6,000 of their own money?h says Jan

Grigsby, chief financial officer at Springhill Medical Center in Mobile,

Ala.

Like Nebraska Methodist, Springhill reaches out to patients before scheduled

procedures with an estimate of what theyfll owe, Grigsby says. For those who

canft pay immediately, the hospital works with lenders to arrange no-interest

payment plans of as long as two years. Staff members also check whether patients

are eligible for charity care from the hospital or if they qualify for

Medicaid.

Many hospitals try to get patients to pay upfront 30 percent to

50 percent of what theyfll owe and some offer discounts for paying early,

says Yaro Voloshin of health-care consultant MedAssets (MDAS). One reason is that they want to avoid the

damage to their reputations that accompanies aggressive debt collection

practices. gOver the years therefs been some stigma about collecting from

patients,h says Zac Stillerman, an executive with the Advisory Board, which

sells software and consulting services to hospitals. gItfs a bit of a third

rail.h

Managers at Nebraska Methodist noticed payment problems getting worse about

seven years ago, when a large employer in the Omaha area introduced a plan with

a $5,000 deductible. gWe would bill a procedure for a patient; the entire amount

would be applied to the deductible,h says Bob Wagner, the hospitalfs director

for revenue cycle. gWe actually got no money.h

Now any patient scheduling a procedure expected to cost more than $500 out of

pocket gets a call from Rempe or another of Nebraska Methodistfs five financial

counselors. The hospital tries to get some payment in advance, but it doesnft

turn away those who canft pay.

Even simply identifying the indigent can help, says Gundling of the

Healthcare Financial Management Association. gFor both the patient and the

facility,h he says, gtrying to collect a debt that canft be paid just wastes

everybodyfs time.h